Bikepacking Central Oregon Mountains in Spring

It's one of those ironies that most bike shop owners don't have leisure to ride bikes long form in the tall days of summer. After 10 years of Clever Cycles, this most technically ambitious of tours I've undertaken marks my embrace of shoulder-season bikepacking, with its more demanding caloric and gear requirements. Maybe I'll progress to actual winter camping. Or maybe instead I'll fly to the southern hemisphere or tropics, naturally with my Brompton. (I'm coming for you, North Sulawesi!)

Bikepacking is the millennial term for what old people called Unsupported Expedition Bicycle Touring. It's going camping by bicycle. I've been at it for only 20 of my 51 years, though not often enough. Before that I was more of a credit-card bike tourist. This is opposite the usual order of operations, age driving most people inside. Also opposite the usual progression is having ridden an oversized 10-speed as a grade schooler, then dropping mostly to 26" wheels in early adulthood, and now embracing the 16" wheels of a Brompton for nearly all my transportation of the last four years, as most of it for the last sixteen. I do sell Bromptons for a living, but I wouldn't blow my vacation riding other than the best bike for my purposes, or at least a very good one, as a promotional stunt. I'll explain more in a follow-up post.

I ride alone because as an introvert, periodic solitude is necessary and restorative. Also part of my agenda is pushing limits of my body and mind into places of some pain and risk, so dragging others along isn't right, just as I'd hold back more fit people. Pumped full of endorphins after several days of sustained exertion, mind focused on the brevity and transience of a life by the steady view of geologic time in the layered rocks, and every condition of roadkill — from bleeding to shattery skew bones — I dissociate, step aside just enough to view my life as if from outside, wrestling demons and angels toward self-acceptance in a broader frame of awareness.

It's been six years of enormous change since my last retreat, seven since my ride down the coast by Brompton, in which a smiling dragonfly hitched a ride on my pack for a day, dying in the night, heralding transformation, passage in the most powerfully cliché fashion.

I didn't come away with any big news, but renewed gratitude to be alive, specifically here in Oregon, so beautiful and nearly wild, so close. It's also affirming that as my physical capacity declines in age and urban indolence, my attitude and technical imagination more than compensates. I had a wonderful time, facing the later days' physical challenges full of easy tears and song, sung in the awful way people with headphones sing. Trees don't complain.

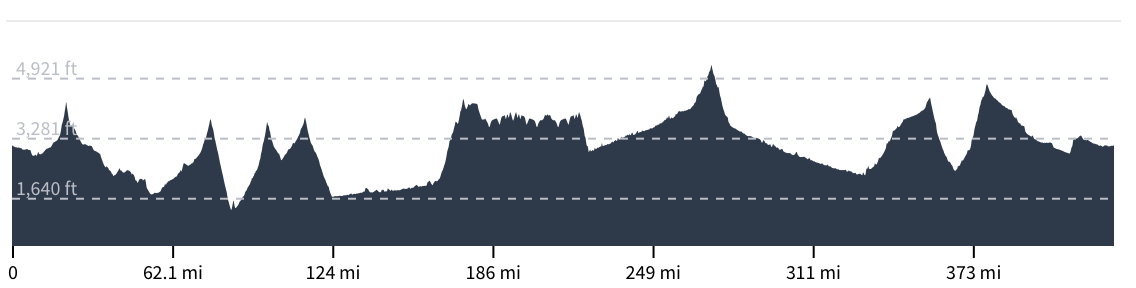

I averaged less than 40 miles (64km) a day, slow compared to past tours. I'm more out of shape than before, but also was surprised at how much more I needed to eat just to stay warm with most early mornings in the 20s (-3C), and a couple rainy days not breaking 40 (4C). Quart of half-and-half or whole chocolate milk for morning coffee? Both! And a quarter-bear of honey per canteen, mixed with milk and chia. I cold-adapted with remarkable speed, leaving off the heat at night and a window cracked when I slept indoors. My raging metabolic furnace left less energy to move down the road each day, though. It was also surprising how much less urgently I needed to bathe along the way, because with careful vent control and layering in the cold, I never broke a proper sweat.

A False Start: Redmond to Madras

I began by riding in the morning to the Portland airport, to catch an Alaska Airlines turboprop flight to Redmond, just 38 minutes over the shoulder of Mt. Hood. This wasn't much more expensive than the 6-hour shuttle bus alternative. As usual, no problem gate-checking the folded bike, without any case or cover whatsoever. The ability to hop on a tiny plane, bus, car, packraft or whatever with no more trouble than a backpack — heck, it can be backpacked — is the benefit easiest to understand of touring with a Brompton over more traditional bike formats.

I rode off from the airport following a route I'd planned using several different online tools. I'd be heading early into rough country of juniper and sagebrush, a string of ghost towns: Ashwood, Kilts, Horse Heaven, with no services or signal, until I hit Service Creek on the John Day River, I hoped by the end of the third day. This way I would eat most of the several days of food I'd packed early, replenishing lighter bags from towns further along the route. My routing tools indicated that there'd be no more than 20 miles of unpaved roads in this segment.

I learned early not to trust my routing tools, because within hours I was pushing the bike through the sticky volcanic mud of a "paved" road, up the side of Grizzly Mountain, all signs suggesting there'd be no improvements as I proceeded steeper and steeper until I hit a tall chained gate, emphatically signed no trespassing, with barbed wire and notice of surveillance. I'd made less than half the progress I'd hoped, and it was an hour before sunset. Maps in doubt, I turned around and improvised a new route, following a jeep track of fist-and-baby-skull -sized rocks under high power lines heading in the right direction roughly. Neither mud nor rocks are favorable to Brompton wheels: slow going, mostly pushing.

Just before sunset the track crossed a pleasant stream lined with trees suitable for hammocking. I pitched camp a little anxiously because I was using so much new gear for the first time, but it came together well, leaving me just enough time in the golden hour to relax, admire some chalcedony stones, and appreciate how beautiful a place I'd come to stop. Filtering water from the stream, I cooked and ate as several deer startled to find me at dusk, gentle showers sweeping through. From long-dry cow poop on the ground, I presume this was summer pasture. I fell asleep early, wondering whether I could salvage my original plans with a few more hours of effort, or whether I'd need to reroute more conservatively. I don't mind going slow offroad, but I need to keep a certain speed to replenish charge on my iPhone/GPS, which runs off the hub dynamo. If my GPS died, food running low in the cold, things might become unpleasant.

Coyotes woke me around dawn. I'd heard the patter of rain on my tarp intermittently all night, but now was a softer sound, and the tarp sagged heavily: snow! I was cozy in my well-insulated hammock, a BoneFire Whisper, but I'd be cold as soon as I got up. I made a few cheery boils for coffee and seeded oatmeal with dried apricots, then struggled to break camp, fingers lame in the chill. Both at night and in the morning, I boiled water to fill my stainless canteen, and tucked it in a wool sock next to my femoral artery for warmth.

With the rocky path covered in snow and slippery, and no idea how long it would snow, my priority became to rejoin pavement. I would beat a strategic retreat down to Madras, where with aid of a data signal I'd re-plan. I lost a lot of elevation dropping into town, and holed up in the Econo-Lodge. The very friendly host recommended she hook me up with a freelance taxi in the morning to help recover time lost and rejoin my original itinerary. I took her up on that, paying a modest fare for a ride out to the summit past Antelope, a new route laid in that stuck to obviously paved roads. Those ghost towns await another adventure in better weather or a mud-optimized bike. The drive out was through beautiful country: if I had more days I'd have been happy to ride them.

Making Up for Lost Time: Antelope to Service Creek

From the summit past Antelope, I dropped thousands of feet in a few miles to the John Day River at Clarno, under partly-cloudy skies with plenty of sun peaking through. I took a very shaky video of the entire breathtaking descent. My thrill at the stunning views on the drop was sobered by awareness I'd need to climb more than I was descending over the day. Even with the half day of rest in Madras, I was feeling pretty sore.

I suffered sweetly climbing out of the river valley up over the pass to Fossil, and then again to another summit past. It was gorgeous, sun and snow flurries freakily intermingling, my spirits high. My knees, pain in which is always my greatest worry and vulnerability on harder rides, bothered me in only the gentlest way. Was it the peppered turmeric, the frankincense, the MSM with glucosamine, or the nightly niacinamide flush with arnica liniment? Or was it that I no longer take NSAIDs at night, to let the healing inflammatory response do its thing while I sleep? A little of all? My knees hurt less than 20 years ago: I'm doing something right.

I stopped a few times to filter water from the rushing roadside stream, and took some videos. I've carried a water filter on previous tours, but somehow seldom used it. This trip was different: I don't think it would even be possible without carrying an absurd weight in water, as distance between accessible taps is too great. Even though cows pooped all around these flows at lower elevations, my filter worked perfectly, all the cold tasty water I could ever want, never a hint of contamination.

I meant to camp at a site called Big Sarvice [sic] Corral, for a fee because showers, and maybe wifi so I could check the forecast? There's no phone signal in these parts. I rode in to check it out: very nice. Confirmed that the showers were hot! But not a soul around, no wifi either. I deliberated whether to make camp leaving a note to whomever might come by later that I was happy to pay, but didn't want to be anxious about such an encounter. I rode a few miles further to Service Creek toward sunset, where, tired and tempted by a restaurant meal, I booked a room. Alas, still no wifi, but I enjoyed the meal and shower.

They pronounced me, for the first of at least six times on this trip, the first bicyclist of the season. As I'd learn more and more along the way, bicycle tourism is an improbably big deal economically out here, with bicycle-friendliness heavily promoted throughout the hospitality sector, rusty cruisers that would kill anybody on these hills propped up against roadside signs. The southern leg is part of the most popular trans-America bicycle route.

Service Creek to Long Creek

Day 4 was easy along the John Day River, cold and heavily overcast with showers. As I've come to expect after a big hard day early on tour, I was slow and weak, dragging along for a few hours at 6-7 mph on the flat. I pitched another free camp just past Kimberly, famous for its stone fruit, preparing for a cold night, this time filling both of my canteens with boiling water to tuck into my bedding. In the morning I shot some video about my gear, some of which I'd made, pleased how well it was performing. I was meeting pretty hard conditions of cold and wet with encouraging ease. Before leaving I fretted alternately that I was over- or under-packing for this trip, but it turns out I nailed it!

Day 5: rained gently all day, as I climbed through Monument to Long Creek. I felt strong and good, buoyed by the evocative scent of pine, the sheep, cattle, horses and indefatigable working dogs thriving in idyllic grassy splendor, and the fascinating rock formations. This whole area is a geologist/paleontologist's mecca, with a 40-million-year fossil record of early mammals allegedly the richest anyplace on the planet. Toward the end of the day, at elevation, the landscape became more somber and cold, with a heart-rending profusion of dead deer ensnared in barbed wire, the stench unavoidable for long stretches.

Rolling late into the tiny town, temperature plunging and little tree cover for camp, I pulled into the sole lodge. The host seemed positively startled to see a bicyclist, or anybody, enter. "It's not season yet!" There were no restaurants or stores open, so I cooked in the room. The clocks hadn't been changed from daylight savings time weeks prior, and the many signs warning me what I was not to do suggested some history of terrible guests.

Calling the Universe's Bluff, and Another Bikepacker!

About half an inch of snow had accumulated in the morning, a little brisk. I promptly headed off in the wrong direction, misreading a sign, and burned away a good hour of mild climbing in my warmest clothes before I realized my error, turning around. Back in town, I stopped again at the market to buy extra calories, as staying warm meant I'd need never to stop moving. I asked if they stocked camping food. They directed me to their dedicated camping supply room: everything I'd need to load up the truck, shoot and field-dress elk! Plus 5-gallon cans of baked beans, vats of shortening, bundles of firewood and propane cylinders, dutch ovens and oil-barrel field stoves, ATV parts, etc. "Camping" is about as ambiguous as "bicycling." I stuck with sardines in oil, honey, jerky from Tillamook, Triscuits, a slab of pepper jack, and some locally milled hot cereal. A customer asked "Are you the crazy son of a gun I saw on that little bicycle yesterday?" "Yes, yes I am! Fugitive from the insane clown circus."

Finally pointed the right way, around 11, I struggled about 10 miles against bitter head and crosswinds up over a ridge separating me from the middle fork of the John Day. Sideways snow flurries hit, progressively thicker and thicker, until near the summit I was pushing the bike in a near whiteout, my balaclava frosted over. Oregon Spring, wow! What would tonight's camping conditions be like?

And then, the grade broke downhill. Downwind below, I saw the swirling mass of snow swell into a bright luminous cloud, with peaks of golden green in the valley. I got back on, and within a few hundred yards of speedy descent, the sun burst forth against a deep blue sky, the road glistening wet. A few minutes and over a thousand feet below at the river, it seemed a balmy 50 degrees (10C), beautiful, meadowlarks singing, the snowy pass so hard to imagine so close in time and space, hardly a puff visible curling over the ridge. I pulled off a few layers, including wool gloves for the first time of the whole trip.

Now I understood why the weather forecasts for this country, the few times I'd been able to consult them, had been so contrary and rapidly changing: every ridge and valley has its own microclimate. For the next hours I stopped every few miles to remove or add clothing, so often did conditions change.

I enjoyed a tailwind for the remainder of the day. Riding upstream, I knew I was gaining elevation, but the gentleness of the grade and the wind made it hard to believe I wasn't descending. Even visually the road seemed to drop, enough that I kept marveling to check that the current beside me flowed contrary. Bald eagles soared over the wild and remote river, with cottonwood, willow and alder flanking. Deer and maybe elk picked their way through gaps in the snow high on the valley walls. This stretch was the farthest I'd get from Portland. It hit me bittersweet that I'd soon be on the return leg.

Later in the afternoon, I spied another person on a bike riding toward me, the first and only of the whole trip, and maybe only the third or fourth other vehicle of the day. Full packs, another tourist! Would I stop to say hi, compare notes about the road ahead? It was a she. Did I recognize her face from Portland? Is that a Salsa Vaya? I rang my bell. She rang hers. Two finger wave, no break in momentum: we passed. Wait, shouldn't I turn around to warn her about the mean climb up to the snowy pass, and how maybe she'd want to pitch camp before that? I mean, if it were me. Nah, mansplainy at best.

I hung my hammock between two grand Ponderosas out of sight of the road. Expecting that I might wake up in snow again, I rushed against fading light to gather enough dry-ish twigs for the evening and morning boils in my chimney kettle. After partly filling one canteen with hot water, I set it in my hammock loosely wrapped in my topquilt while I boiled more to top it off. When I reached for it again, I panicked to discover that it had tipped over, and the headspace had pressurized the contents, forcing a few cups of water out past the gasket lid into my down! Wet down has negligible insulation value. Cursing my carelessness, I shook things out as well as I could. When I woke, ice glazed my tarp under a bright blue sky, but hey: no hypothermic death in the backcountry all alone invisible with no phone signal, this time.

Homeward

This wasn't the last day of the tour, but psychologically it was an end. The return leg always feels anticlimactic to me in its challenges and rewards as an adventure. Leaving the middle fork, I rejoined Highway 26, smooth and well-trafficked, with margins freshly swept of winter's gravel. This same highway is Powell Boulevard in Portland, from which I live only a bike minute away. I'd proven my body and my gear: all that remained was to adjust my headspace.

By the final pass on day 9, over Ochoco Summit, I couldn't go an hour without tearing up in gratitude for one blessing or another: people I love living and dead, familiar and estranged. I thanked my Summer camp counselors of 40 years ago who taught me to carry my weight through wild places, listening to the forest, leaving no trace. Snow covered the pass. Wildfire had passed through in a recent year, blackening younger pines stark against the white. I likened the transcendent beauty of this wilderness, and the physical trials I'd engaged, to that cleansing fire, culling the tangled underbrush and weaker little trees of my soul.